With the spread of materials informatics (MI), DFT calculations, and molecular dynamics simulations, the number of opportunities to input molecular structures on a computer is rapidly increasing.

The SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) notation, which treats molecular structures as strings of characters, is often used in this case. Although many chemistry software programs allow for conversion between molecular structures and SMILES, by learning the skill of "writing it yourself," you can check for errors in your data and quickly prepare structures for calculations.

In this article, we will introduce how to write SMILES, with the aim of enabling you to freely express anything from simple molecules to slightly complex ring structures.

1. SMILES notation

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) is a notation for expressing molecular structures as "character strings." The basic rule of SMILES is to omit hydrogen atoms and to describe the connections between atoms in a single stroke. Here, we will explain the rules little by little while drawing specific structures.

1-1. SMILES of linear molecules

First, we introduce the SMILES notation for linear molecules.

For linear molecules composed only of single bonds, the SMILES representation is obtained simply by writing the element symbols in order from one end of the molecule to the other.

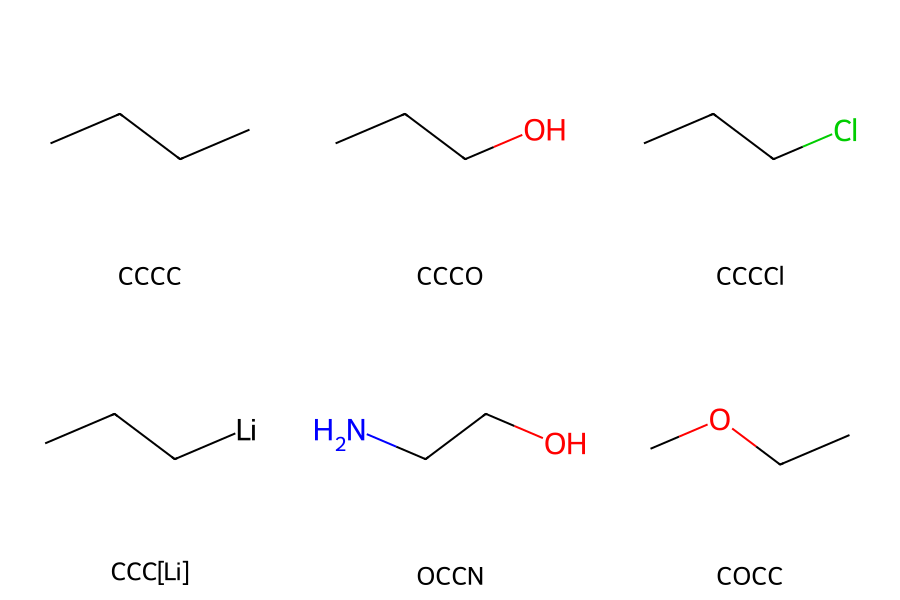

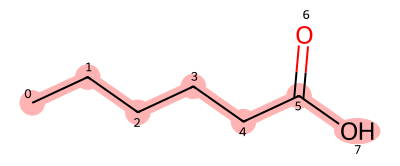

Elements that frequently appear in organic chemistry—B, C, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, and I—can be written directly, whereas other elements must be enclosed in square brackets [ ]. A concrete example is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structure and SMILES of a linear molecule

[Note] SMILES are not uniquely determined.

Even for the same molecular structure, the SMILES representation can differ depending on which atom is chosen as the starting point.

For example, in the case of propanol, both CCCO and OCCC are valid SMILES strings.

Although there exists a representation called Canonical SMILES, which uniquely defines a molecule, we will not consider it for now and will simply focus on writing SMILES freely.

So far, we have drawn molecules consisting of only single bonds. If there are bonds other than single bonds, insert the following bond symbols between atoms.

Single bond: - (usually omitted)

Double bond:=

Triple bond:#

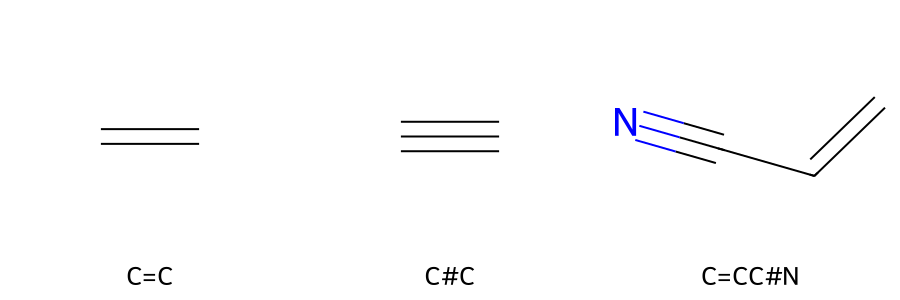

Using these, Figure 2 shows a specific example of the structure and SMILES of a linear molecule with multiple bonds.

Figure 2. Structure of a linear molecule with multiple bonds and SMILES

1-2. SMILES of molecules with branched structures

From here, the examples become slightly more complex.

When writing SMILES for branched molecular structures, first choose a “main chain” that can be drawn as a continuous path.

The main chain can be chosen arbitrarily, but in many cases it is more convenient to select the longest possible chain.

After that, branches are written by enclosing the branched structure in parentheses ( ) immediately after the atom from which the branch originates.

Let us look at a concrete example.

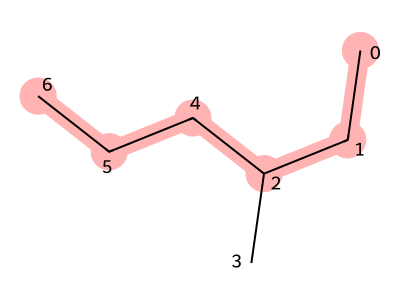

First, we draw the molecular structure of 3-methylhexane. Each atom is assigned an index.

We begin by choosing the main chain. The structure connecting atoms with indices 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 forms a long linear chain, so we select this as the main chain.

We then write the SMILES for the main chain. In this case, it is CCCCCC.

Next, since a methyl group branches from the third carbon (atom index 2), we write (C) immediately after the third carbon in the SMILES string.

This gives the final SMILES representation: CCC(C)CCC

Figure 3. Structure of 3-methylhexane (red part is the stem)

When a molecule has multiple branches, each branch is written by enclosing the branched structure in parentheses ( ) immediately after the atom from which it branches.

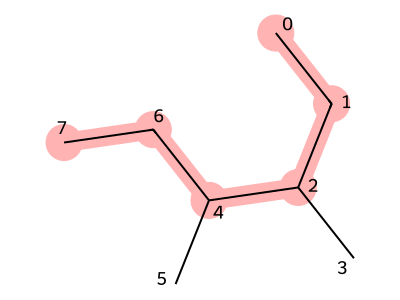

As an example, let us write the SMILES representation of 3,4-dimethylhexane, shown below.

As in the case of 3-methylhexane, we first choose the main chain.

In this example, the structure connecting atoms with indices 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 is selected as the main chain, and the corresponding SMILES for the main chain is CCCCCC

. Since methyl groups branch from the third and fourth carbons, we write (C) immediately after the third and fourth carbons in the SMILES string.

This gives the final SMILES representation: CCC(C)C(C)CC.

Figure 4. Structure of 3,4-dimethylhexane (red part is the trunk)

Even when multiple branches originate from the same atom, they can be written consecutively after the branching atom without any issues.

For example, in the case of 3,3-dimethylhexane, the SMILES representation is CCC(C)(C)CCC.

When a branch is connected by a bond other than a single bond, the bond information is also enclosed in parentheses ( ).

As an example, let us write the SMILES representation of hexanoic acid. As before, we first choose the main chain. In this case, the substructure connecting atoms with indices 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 is selected as the main chain, and the SMILES for the main chain is CCCCCO. Since a double-bonded oxygen branches from the terminal carbon, we place (=O) immediately after that carbon, resulting in the final SMILES representation: CCCCC(=O)O.

Figure 5. Structure of hexanoic acid (red part is the stem)

1-3. SMILES of molecules with cyclic structures

Next, we will introduce how to write molecules with ring structures such as cyclohexane and benzene. Ring structures are thought of as "atoms that are separated and bonded together to form a ring," and the bond is represented by adding the same number after the atoms that bond together.

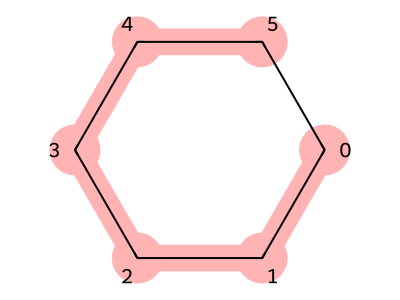

First, let us consider cyclohexane, a simple molecule with a ring structure.

If we view the main chain of cyclohexane as the structure connecting atoms with indices 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (SMILES:CCCCCC), cyclohexane can be understood as a molecule in which the two terminal atoms of this chain (indices 0 and 5) are connected to each other.

By assigning the same ring index 1 to the first and last carbons involved in this bond, we obtain the SMILES representation of cyclohexane: C1CCCCC1.

Figure 6. Cyclohexane structure (red part is the trunk)

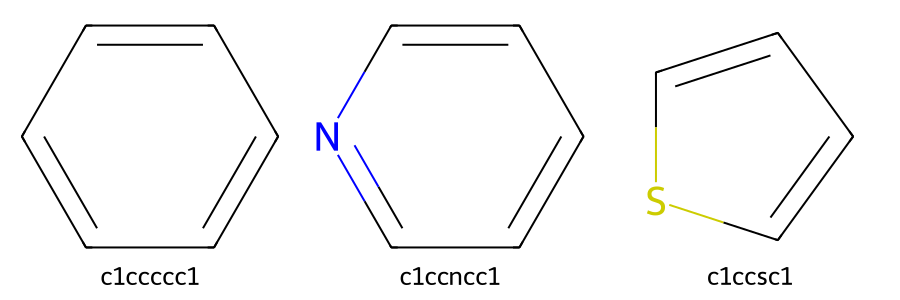

In the case of benzene, the double bonds can be explicitly written, resulting in the SMILES representation C1=CC=CC=C1. However, atoms that are part of an aromatic system can also be written in lowercase letters with the bond types omitted, so benzene can alternatively be written as

c1ccccc1. The same rule applies to heteroaromatic rings. For example, pyridine can be written as c1ccncc1, and pyrrole can be written as c1ccsc1.

Figure 7. Structures and SMILES of aromatic compounds

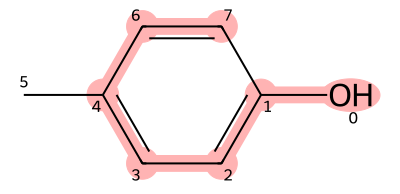

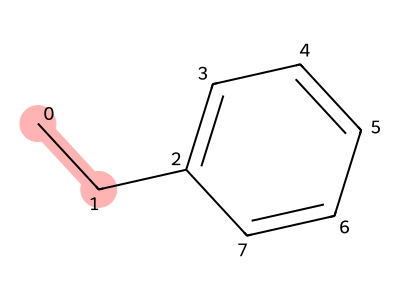

The SMILES representation of a ring with substituents can be written by applying the concepts introduced so far.

As an example, let us consider p-cresol, shown below.

As before, we first choose the main chain. In this case, the substructure connecting atoms with indices 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 is selected as the main chain.

Since the carbon atoms with indices 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 are aromatic carbons, they are written in lowercase letters, giving the SMILES for the main chain as Occcccc.

Next, because the atoms with indices 1 and 7 are connected to form a ring, we assign the same ring index 1 to the first and last carbons.

Furthermore, since a methyl group branches from the fourth carbon (atom index 4), we add (C) after that carbon.

This results in the final SMILES representation: Oc1ccc(C)cc1.

Figure 8. Structure of p-cresol (red part is the trunk)

By this point, you should be able to write SMILES representations for ring structures with substituents.

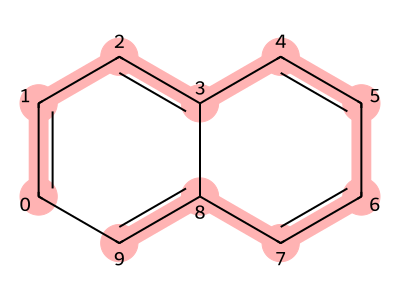

Next, we explain how to write SMILES for molecules with fused ring systems, in which multiple rings share atoms, using naphthalene as an example.

As before, we first choose the main chain and write its SMILES representation.

In this case, we select the substructure connecting atoms with indices 0 through 9 as the main chain.

Since all of these atoms are aromatic carbons, the corresponding SMILES is written as cccccccccc.

Next, because the first and last carbons (atom indices 0 and 9) are connected to form a ring, we assign a ring index to them.

This gives the SMILES representation c1ccccccccc1.

In addition, there is another bond between the fourth and ninth carbons (atom indices 3 and 8).

Since the ring index 1 has already been used, we assign a different number, 2, to this bond.

This results in the final SMILES representation: c1ccc2ccccc2c1.

More complex fused ring systems, such as anthracene, can be written in the same manner.

Figure 9. Naphthalene structure (red part is the trunk)

1-4. Polymer SMILES

There are no strict rules for describing polymers themselves in SMILES notation. However, when performing MI or molecular dynamics simulations, there are times when you want to handle polymer-like structures such as oligomers as input data. Here, we will introduce a method for representing pseudo-polymer structures in SMILES.

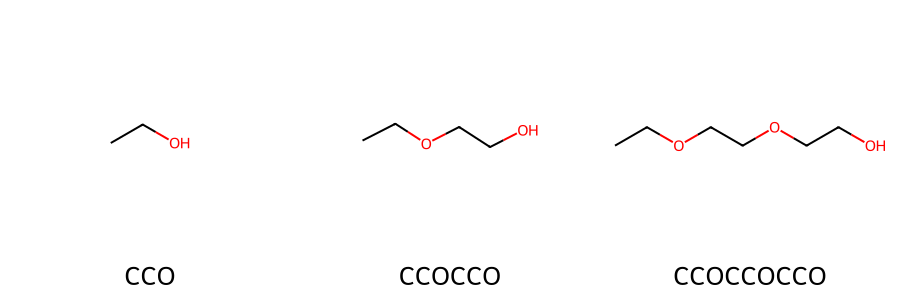

First, let us consider the SMILES representation of polymers without side chains.

Here, we focus on the SMILES notation for poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO).

We begin by writing the SMILES for the repeating unit of PEO, which is CCO.

Repeating this unit n times gives the SMILES representation of an n-mer of PEO.

For example, the dimer is written as CCOCCO, and the trimer as CCOCCOCCO.

Figure 10. PEO structure and SMILES

So far, this shouldn't be too difficult. The problem is figuring out the SMILES of a polymer with side chains. If you just write the SMILES of the repeating structure of a polymer with side chains haphazardly, just repeating it like PEO above won't result in the SMILES of a polymer, so you need to think about which part is the backbone.

Here, we consider polystyrene as an example of a polymer with side chains.

The repeating unit of polystyrene can be written as a SMILES string by treating all atoms as part of the main chain. However, in that case, simply repeating the unit n times does not produce the SMILES representation of an n-mer, as shown above.

By defining only the portion that becomes the polymer backbone as the main chain, SMILES representations can be constructed easily even for polymers with side chains.

In polystyrene, the carbon atoms with indices 0 and 1 in the structure shown in Figure 11 form the backbone upon polymerization. Therefore, we select only these two atoms as the main chain.

The benzene ring is then treated as a branch, and the SMILES representation is written as CC(c1cccc1).

With this SMILES representation, repeating the unit n times yields the structure of an n-mer of polystyrene.

Figure 11. Repeating structure of polystyrene (red part is the trunk)

2. Advanced SMILES notation

I think you can write the SMILES of many molecules using the information introduced so far. However, there may be times when you want to write geometric isomers, optical isomers, or compounds with charges or radicals. This section will introduce these methods.

2-1. SMILES of molecular structures with geometric isomers

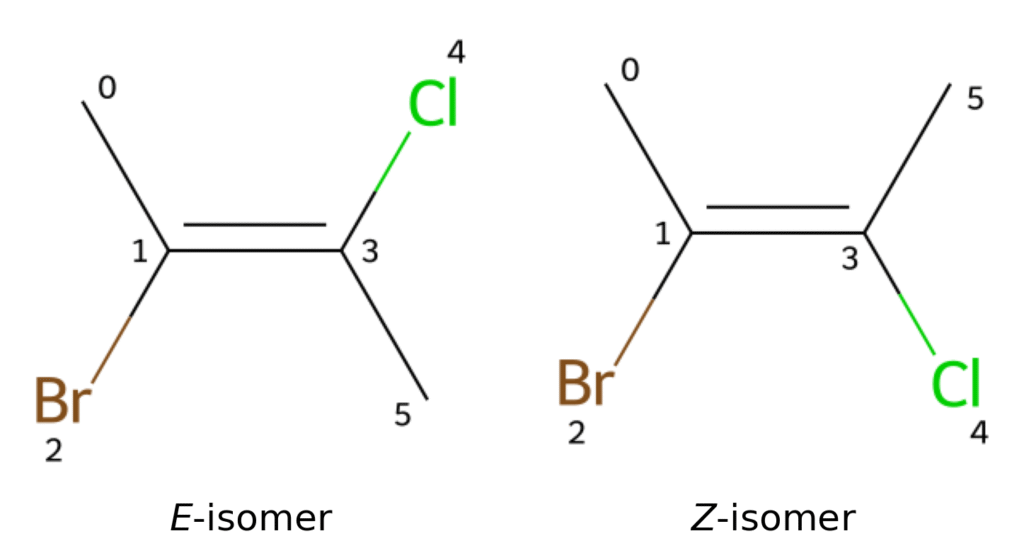

To distinguish cis/trans or E / Z isomers around a double bond, SMILES uses the bond direction symbols / and \. These symbols can be understood visually: if a bond extends from the lower left to the upper right, / is used, whereas if it extends from the upper left to the lower right, \ is used. Here, we consider 2-bromo-3-chloro-2-butene as an example.

This compound has two geometric isomers, the E and Z forms, as shown in Figure 12.

In the E isomer, the bond between atoms with indices 0 and 1 extends from the upper left to the lower right, so \ is used for that bond.

In addition, the bond between atoms with indices 3 and 4 extends from the lower left to the upper right, so / is used.

As a result, the SMILES representation is C\C(Br)=C(/Cl)C. In contrast, for the Z isomer, the bond between atoms with indices 3 and 4 extends from the upper left to the lower right, so / is used.

The corresponding SMILES representation is C\C(Br)=C(\Cl)C.

Alternatively, one can focus on the substituents with higher priority:

if they are on the same side of the double bond, the same symbol / / is used, whereas if they are on opposite sides, different symbols / \ are used.

Using this rule, the SMILES representations can be remembered as E isomer :CC(/Br)=C(\Cl)C, Z isomer :CC(/Br)=C(/Cl)C.

Figure 12. Geometric isomers of 2-bromo-3-chloro-2-butene

2-2. SMILES of molecular structures with optical isomers

To distinguish R/S configurations in molecules with a chiral center, SMILES uses the @symbol.

The chiral atom is enclosed in square brackets [ ], and either @ or @@ is written immediately after it.

This notation indicates the relative arrangement of the three remaining substituents bonded to the chiral center, as viewed from the atom written immediately before the chiral center in the SMILES string, following the order in which the substituents appear in the SMILES notation.

The symbol @ indicates a counterclockwise arrangement, whereas @@ indicates a clockwise arrangement.

Note that when an atom is not enclosed in square brackets [ ], hydrogen atoms are automatically added to satisfy the appropriate valence.

However, when representing optical isomers, the atom must be enclosed in [ ], and therefore hydrogen atoms must be explicitly specified where necessary.

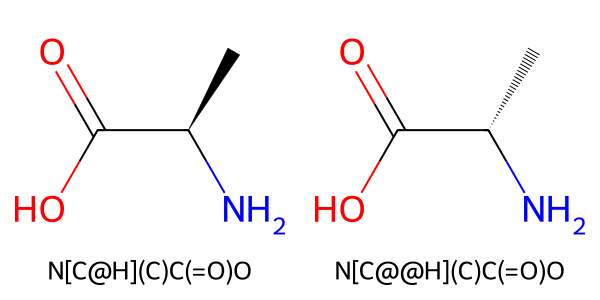

Let us examine alanine as a concrete example.

The SMILES representation of alanine can be written as NC(C)C(=O)O. In this SMILES string, the chiral carbon is the second character, C. The atom written immediately before this chiral carbon is N; therefore, when viewed from N, we determine whether the three substituents—H,C, and C(=O)O—are arranged in a clockwise or counterclockwise manner.

In the structure shown on the left in the figure below, the arrangement is counterclockwise, so the chiral center is written as [C@H]. In the structure shown on the right, the arrangement is clockwise, and the chiral center is written as [C@@H].

Figure 13. SMILES of alanine optical isomers

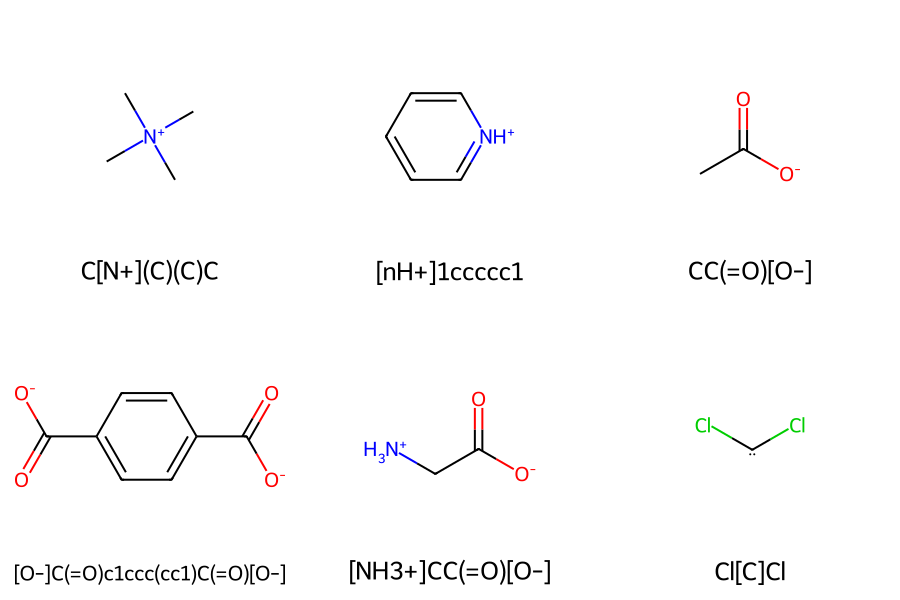

2-3. SMILES of molecular structures with charges and radicals

In general, atoms that frequently appear in organic chemistry can be written without enclosing them in square brackets [ ].

In this case, hydrogen atoms are automatically added to satisfy the appropriate valence.

However, when an atom carries a charge or is a radical, its valence changes, and therefore the atom must be enclosed in [ ]. By doing so, hydrogen atoms are no longer added automatically.

A + symbol is written after the element symbol for a cation, and a - symbol is written for an anion, while no additional symbol is written for radicals.

Below, we present several examples of SMILES representations for compounds that carry charges or radicals.

Figure 14. Structures and SMILES with charges and radicals

3. Summary

This article introduced the essentials of writing SMILES from scratch. Being able to read and write SMILES on your own has great practical benefits, such as being able to detect data errors and quickly correct them. Of course, it's also important to be flexible and use existing tools for complex structures. We hope this article will lower the hurdles to learning SMILES and help accelerate your daily research activities.