Introduction

In the R&D fields of materials science, chemistry, and drug discovery, atomistic and molecular simulations have become established as a foundational technology. They are crucial for elucidating material properties and reaction mechanisms from a microscopic perspective. However, for full-scale utilization in R&D, the trade-off between "accuracy," "computational cost," and "versatility" has always been a significant barrier.

For instance, first-principles calculations (ab initio calculations) enable highly accurate predictions based on quantum mechanics, but their computational cost is extremely high. Even utilizing supercomputers, the practical limit is around "several hundred atoms for several picoseconds". Consequently, it has been difficult to track phenomena requiring long time scales (such as interface reactions or ion diffusion) or phenomena with sizes beyond the nanoscale (such as realistic nanoparticle catalysts).

On the other hand, molecular simulations based on classical mechanics can perform large-scale calculations of "millions of atoms for several microseconds" by using simple functions (such as harmonic oscillators or Lennard-Jones potentials). However, their accuracy and scope of application depend heavily on the design of parameters (force fields). Tuning force field parameters requires deep expertise and a lot of trial and error, and it is not uncommon for development to take years.

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) are currently attracting rapid attention as a technology to resolve this long-standing dilemma. In this article, we will explain the technical background behind MLIPs, which are transforming the field of materials development, from three perspectives: Evolution of Architecture, Quality and Diversity of Training Data, and Model Verification Methods, while also highlighting the latest research trends.

(1) Evolution of MLIP Architecture

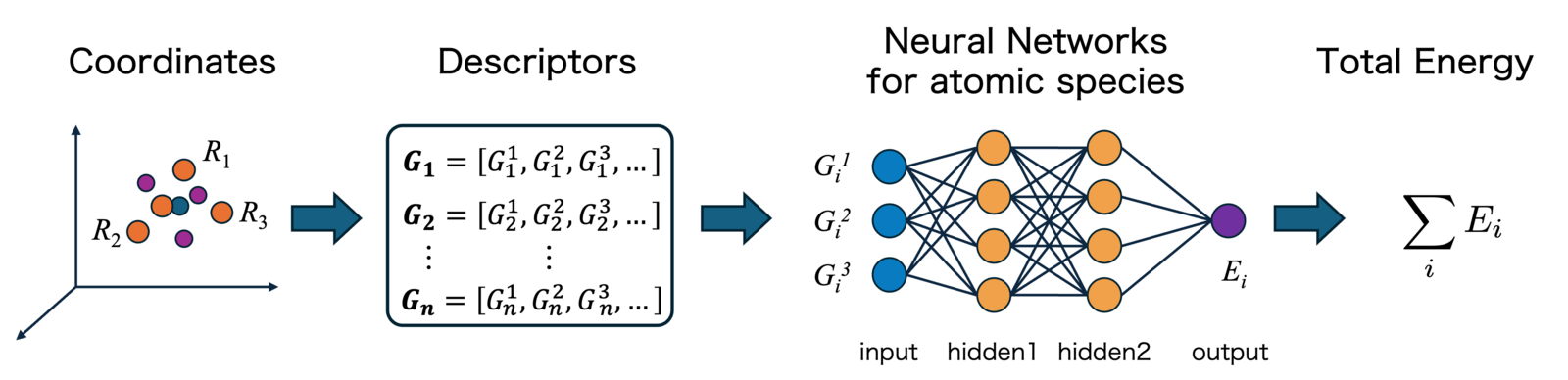

MLIPs are force fields in which a machine learning (ML) model learns the potential energy surface using highly accurate energy and forces generated by first-principles calculations as "training data".

More specifically, given the atomic coordinatesR= {r1,r2, …,rN} and element typesZ, the machine learning model infers the total potential energy E of the system and the forces acting on each atom Fi= – ∇i E . In conventional first-principles calculations, electronic structure calculations (SCF cycles) and the subsequent calculation of energy gradients (forces) are major bottlenecks. MLIPs replace this entire workflow with fast ML model inference, achieving speedups of tens of thousands to tens of millions of times while maintaining accuracy comparable to first-principles methods.

The "architecture" of MLIPs refers to the "design structure of the machine learning model" that converts geometric information—such as atomic coordinates and element types—into features that a computer can process, and ultimately map them to the predicted energy. The development of MLIPs has gone hand in hand with advances in how atomic configurations are represented within a model efficiently and in a way that respects physical requirements such as invariance and equivariance.

Descriptor-based MLIPs (Early Approach)

Early machine learning potentials did not learn atomic coordinates directly. Instead, they converted the local atomic environment within a cutoff sphere around each atom into a vector called a “descriptor,” using fixed analytical formulas, and then fed these descriptors into a neural network. By physical law, the potential energy of an atomic system is invariant under “translations”, “rotations”, and “permutations” of identical atoms. This "Invariance" cannot be achieved using raw coordinate values as input, so it must be ensured during descriptor design.

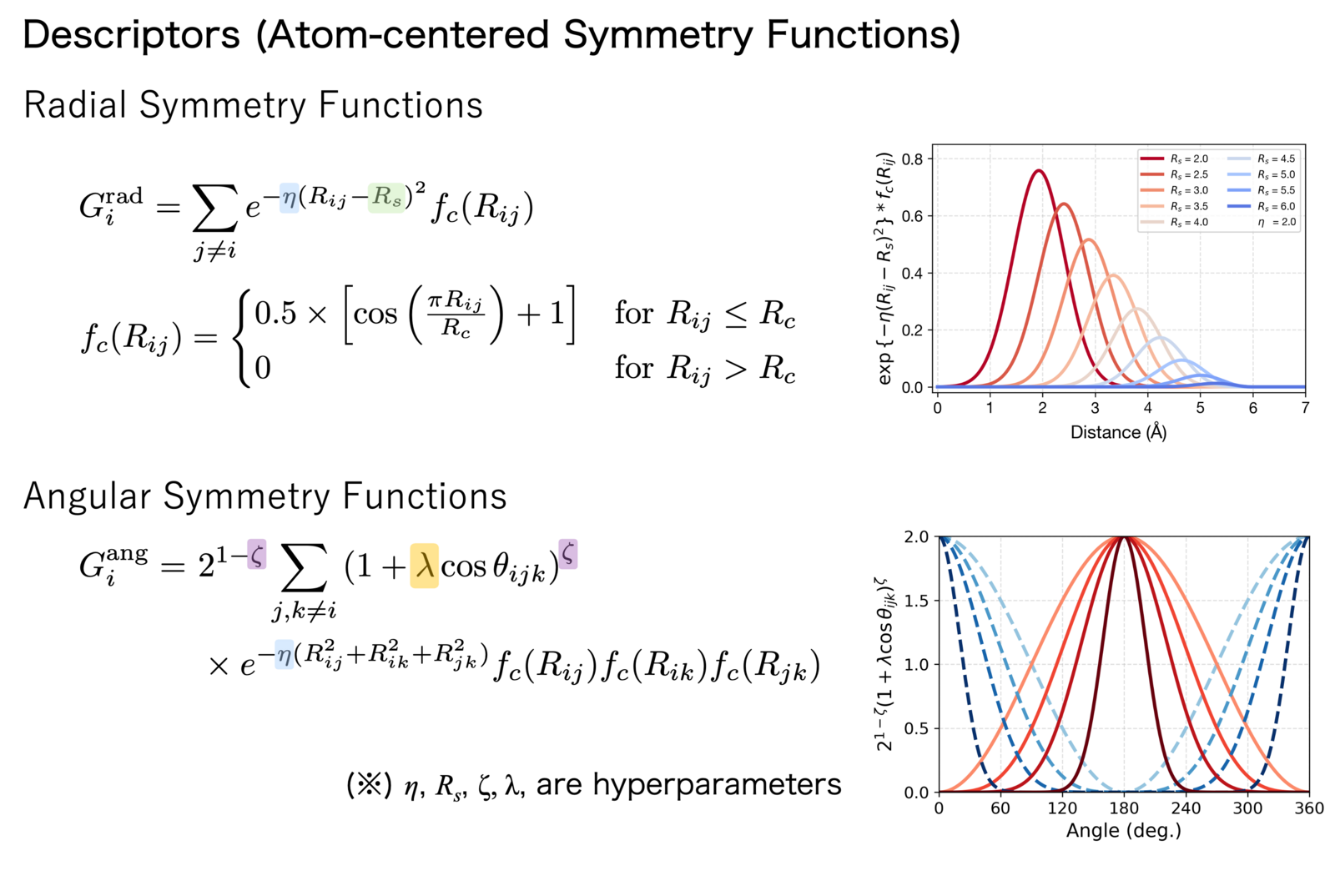

Figure 1: Overview of Descriptor-based Machine Learning Potential

A pioneering study in this field is the Behler-Parrinello Neural Network proposed by Behler and Parrinello in 2007[1]. They employed Atom-Centered Symmetry Functions (ACSF) as descriptors, which express relative information such as interatomic distances and bond angles using Gaussian functions.

Figure 2: Descriptor functions used in Behler-Parrinello type Neural Network Potentials

Another representative descriptor is SOAP (Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions) proposed by Bartók and co-workers[2]]. SOAP represents the local atomic environment by expanding the neighbor density in spherical harmonics and then taking inner products of the expansion coefficients, which mathematically guarantees rotational invariance.

However, challenges remained due to the manual hyperparameter tuning and the lack of element parameterization, which necessitated defining individual descriptors for every element combination. This led to a combinatorial explosion in descriptor dimensionality as the number of species increased, making the method computationally infeasible for multi-component systems

MLIPs based on Graph Neural Networks

Currently, Graph Neural Networks (GNN) are becoming the standard, especially for universal MLIPs. PFP, provided in our general-purpose atomistic simulator "Matlantis," also adopts this technology

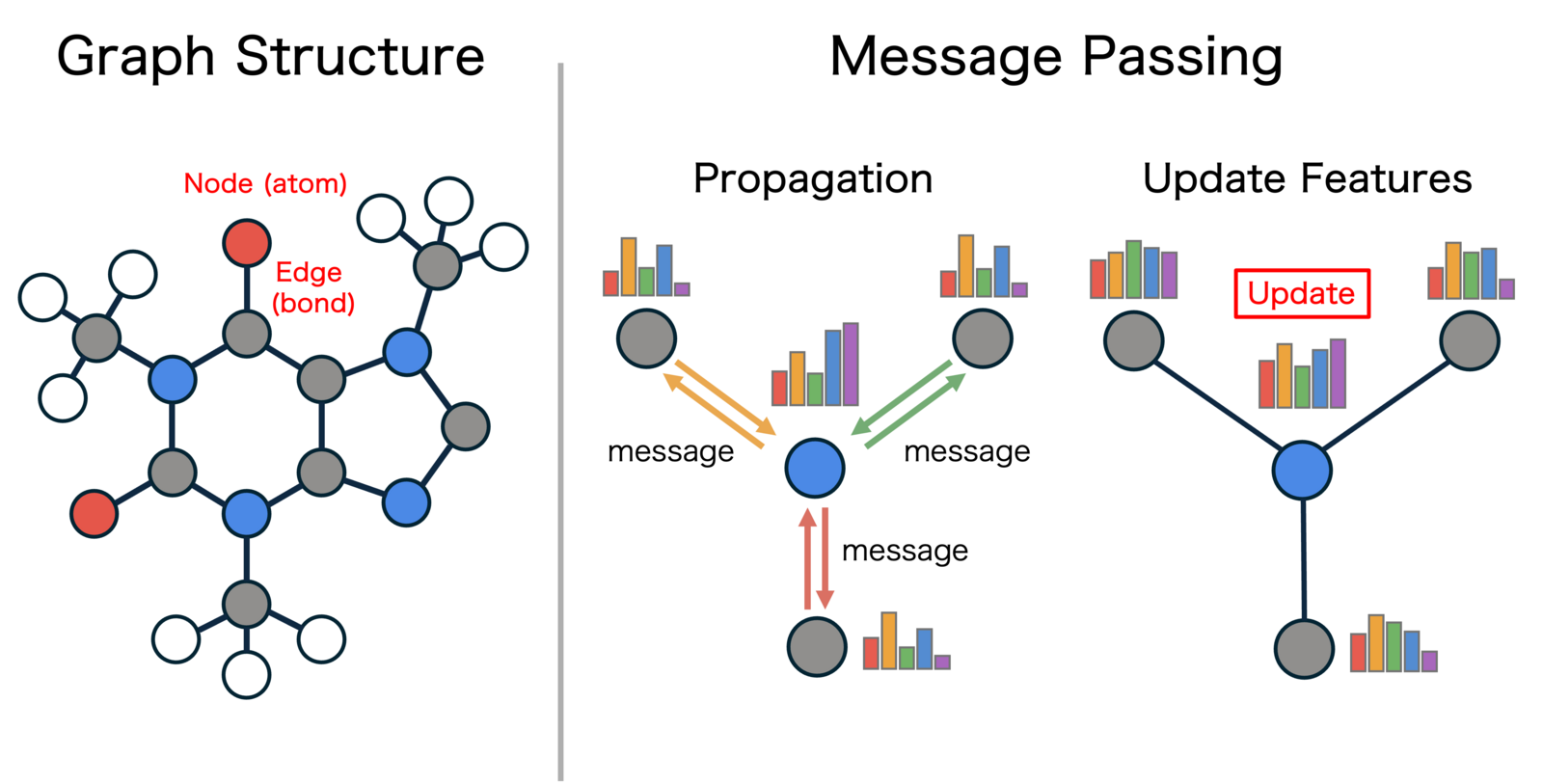

Figure 3: Graph representation of a molecule and the Message Passing mechanism

In graph neural networks, a material is represented as a graph, where atoms are treated as nodes and interatomic interactions (bonds) are treated as edges. The key difference from descriptor-based approaches is that the features representing the local environment of atoms are not manually designed by humans but are learned by the model itself as "Embeddings" through the training process. This allows the machine learning model to efficiently represent chemical similarities between elements in the feature space, enabling efficient and high-precision modeling even for complex systems where many types of elements coexist.

Furthermore, the core of the Graph Neural Network is a mechanism called Message Passing (MP). This is a system where neighboring atoms exchange information (messages) with each other, and by aggregating that information, the embedding representation of each atom is iteratively updated. This allows each atom to indirectly incorporate information from atoms further away, not just its local environment, making it possible to acquire representations that reflect the chemical properties and structural characteristics of the entire system.

From “Invariant” to “Equivariant”

A key aspect of the evolution of GNNs is the different ways they handle geometric information in atomic systems such as rotations and translations. Specifically, it can be classified into two categories: invariant and equivariant methods [3].

- Invariant Message Passing:

Early GNN models exchanged only scalar quantities (values that do not change even if the coordinate system is rotated), such as interatomic distances, as messages. While the calculation is simple, the relative direction of atoms (= vector) is not treated as a feature, limiting the geometric expressive power.- Representative examples: SchNet (2017), AIMNet (2019), DimeNet (2020)

- Equivariant Message Passing:

In addition to scalars, "equivariant features (quantities that rotate themselves in response to the rotation of the coordinate system)," such as vectors and higher-order tensors, are propagated as messages. Since the relative orientation of atoms can be incorporated into features, data efficiency and structural representation capability are significantly improved compared to invariant MP methods.- Representative examples: TeaNet (2019) (the predecessor of PFP, NequIP (2021), Mace (2022), Allegro (2023), UMA (2025)

(2) Collection of Training Data

In creating an MLIP, the collection of training data is even more critical than the selection of architecture. To develop a practical and robust universal model, it is not enough to simply gather a large volume of first-principles data. The key is how efficiently and comprehensively one can sample the vast chemical and structural space because the quality of the dataset ultimately determines the accuracy and usability of the MLIP

The Problem of Datasets Biased Toward Equilibrium States

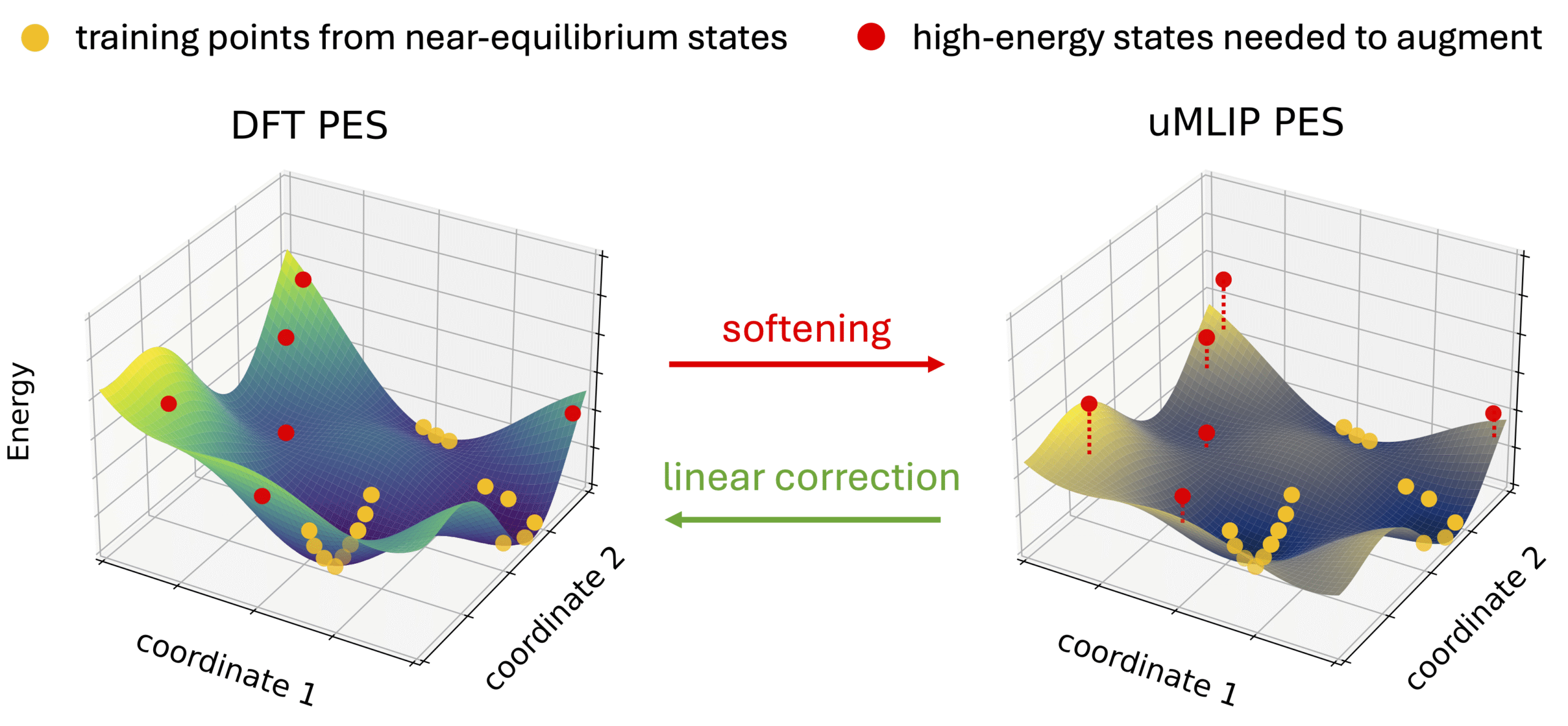

In conventionally existing public datasets like the Materials Project, data near "equilibrium structures" that are energetically stable often account for the overwhelming majority. According to research by Deng et al.(2024), universal MLIPs (e.g., M3GNet, CHGNet, MACE, etc.) trained on such datasets biased near equilibrium points cause a phenomenon called "Systematic Softening" of the potential.

Figure 4: Softened potential energy surface of a universal MLIP(Source: Deng et al., “Overcoming systematic softening in universal machine learning interatomic potentials by fine-tuning”, licensed underCC BY 4.0)

This is a phenomenon where the curvature of the potential energy surface is underestimated, leading to a systematic underestimation of energy and interatomic forces, especially in regions far from the equilibrium state. This leads to the following issues:

- Underestimation of surface and defect energies

- Underestimation of phonon frequencies

- Underestimation of ion migration barriers (battery materials, etc.)

- Failure of molecular dynamics simulations at high temperatures

To address this problem, it is essential to intentionally include non-equilibrium (high-energy) and distorted structures in the training data. In fact, Deng et al. also show that the potential softening problem can be improved by adding just a few points of high-energy structure data for additional training.

Importance of Including Diverse Structures in the Dataset

The systematic softening of the potential mentioned in the previous section was mainly caused by the training data being too concentrated near stable structures. To develop practical MLIPs, it is becoming proven that not only the amount of data but also the "quality and diversity of the dataset" that balances the coverage of structural space is important.

A good example is the MatPES study by Kaplan et al.(2025). This study reported that a model trained on a relatively small dataset of about 400,000 structures achieved performance equal to or better than a model using the massive "OMat24" dataset containing about 100 million structures.

How could a dataset with 1/250 the amount of data deliver equal or better performance? The key lies in the breadth of the structural space covered by the dataset.

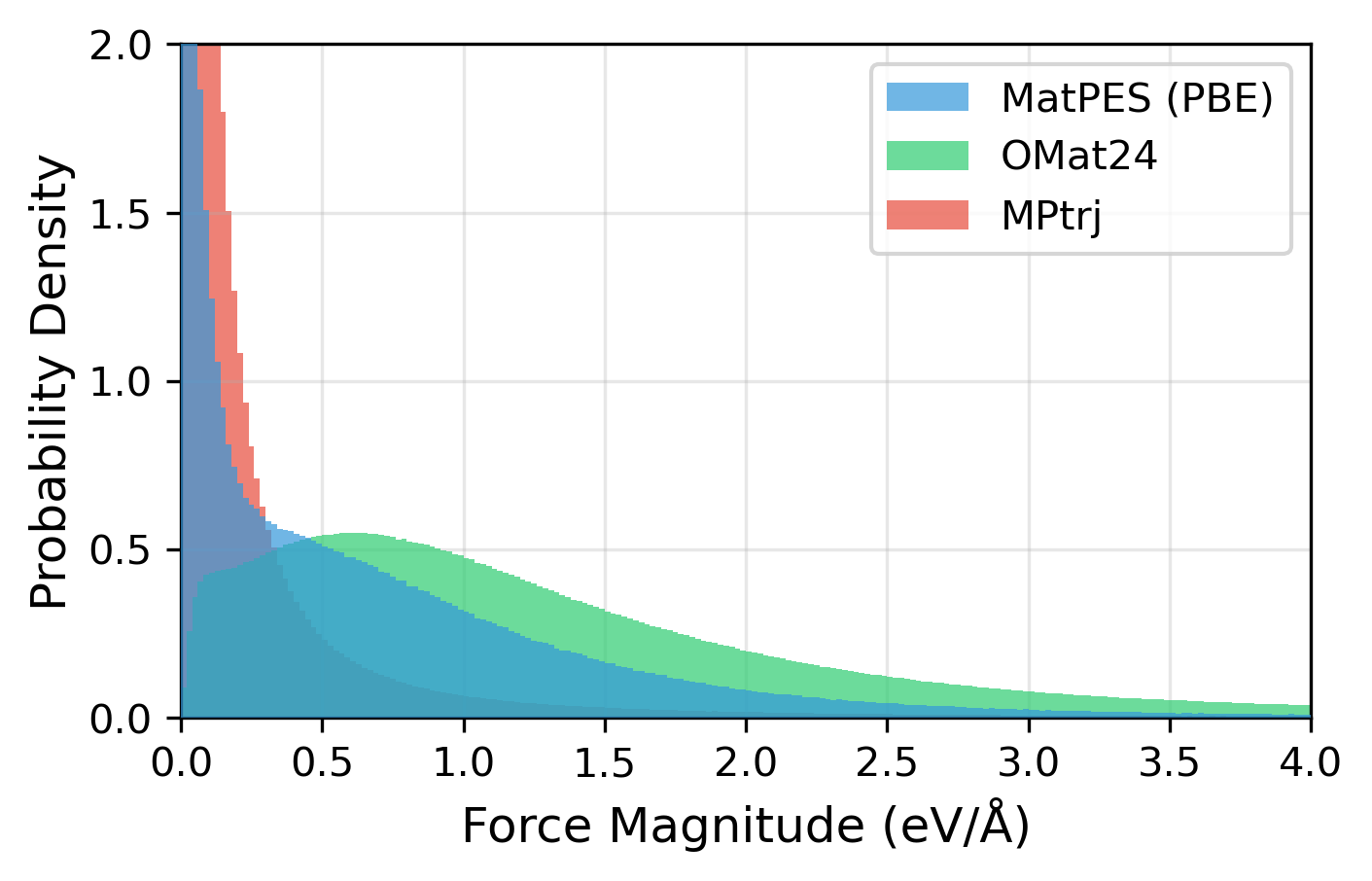

Figure 5: Distribution of structures and forces contained in MatPES (PBE)[6], OMat24[7], MPtrj[8] datasets. While OMat24 is dominated by data in regions with large forces far from equilibrium, MPtrj is concentrated in regions with small forces near equilibrium. MatPES is characterized by balanced coverage of both regions. The figure is created by the author based on Fig. 2 of Kaplan (2025) Fig2.

The MPTrj (Materials Project) dataset consists of trajectory data from structural optimization calculations, so it has the problem that the majority of the data is biased near low-energy equilibrium points. In contrast, the OMat24 dataset contains a large amount of first-principles molecular dynamics data, providing abundant high-energy configurations, but with relatively low sampling density around equilibrium.

MatPES, on the other hand, was constructed with an emphasis on balancing data near equilibrium with moderately off-equilibrium configurations. It also employs a sampling method called “2DIRECT” to select a subset of data with minimal structural and chemical redundancy. As a result, despite being a relatively small dataset of about 400,000 structures, it achieved performance equal to or better than models trained on OMat24, which contains about 100 million structures

This finding suggests that, rather than training on countless similar stable structures, it can be far more data-efficient (and cost-effective) to train on a balanced set that covers previously unseen regions and physically important regimes of the configuration space.

Sampling Strategies to Ensure Structural Diversity

Then, how can "diversity" be included in a dataset? In a review published in Chemical Reviews by Kulichenko et al. (2024) [9], the following sampling strategies are proposed to ensure structural diversity:

- Active Learning: Focus first-principles calculations and retraining on regions where the model’s predictive uncertainty is high. This helps remove human bias while maximizing data diversity at minimal cost.

- Rare Event Sampling Methods:Utilize Metadynamics, uncertainty-driven dynamics that use model uncertainty as a bias, and transition state sampling to explore regions difficult to reach with conventional molecular dynamics simulations.

Data Collecting Strategy in Matlantis

The “importance of non-equilibrium and unstable structural data” discussed above has been re-emphasized by recent studies from 2024–2025. However, an early example of putting this strategy into practice and successfully productizing it is PFP, the model deployed in Matlantis.

In thePFP paperpublished in Nature Communications in 2022 [10] , the development team describes a clear strategy: "We aggressively gathered a dataset containing unstable structures".

More specifically, at the PFP development stage (2021), the developer intentionally covered a range of unstable states through approaches such as the following [11, 12].

- Randomly substituting elements within crystal structures

- Generating disordered structures in which diverse elements coexist

- Creating off-equilibrium states by changing temperature and density

- Covering a wide chemical space by utilizing high-temperature molecular dynamics simulations and active learning

This dataset-construction philosophy emphasizing not only the amount of data but also its quality (diversity) is a key reason why PFP can demonstrate high versatility and robustness even for unknown materials and complex chemical reactions.

Another advantage of the PFP dataset, compared with many public datasets, is that it has been continuously updated since the Matlantis service launched in 2021, incorporating feedback from customers engaged in real-world materials development.

(3) How to validate MLIPs

After building a model, another crucial challenge is how to validate its correctness. Traditionally, evaluation has focused on prediction errors for energies and forces on static structures (e.g., MAE). However, these metrics alone may not prevent unphysical behavior during simulations, such as structural collapse or abnormal dynamics.

To address these challenges, recent validation practices are shifting away from “static errors” and toward “simulation outcomes and predicted physical properties”. For example, the latest benchmarks such as MLIP Arena (2025)[12] andCHIPS-FF (2025)[14] both place physical plausibility at the center of their evaluation criteria.

- MLIP Arena: Beyond standard error-based regression metrics, it checks the quality of features as a physical model, such as whether the law of conservation of energy is observed and whether the potential curve shows unnatural behavior when interatomic distances become extremely close. It also uses stress tests, such as whether simulations fail under extreme high-temperature and high-pressure conditions, as benchmarks.

- CHIPS-FF: It evaluates the reproducibility of concrete material properties required in the real-world materials development, such as elastic constants, phonon band structures, and defect formation energies.

PFP in Matlantis is also provided as a physically valid general-purpose force field through validation not only in terms of energy and force prediction accuracy, but also through comprehensive evaluations across a wide range of material properties. Some of PFP’s validations are publicly available on the pages below, so please take a look.

- Verification of Predicted Performance of PFP (Liquid density, phase diagrams, etc)

- Comparison with Open Source MLIP (Lattice thermal conductivity, surface energy)

- PFN Blog: Benchmark surface energies with PFP

- PFN Blog: Lattice thermal conductivity calculation with PFP

Summary

In this article, we explain the following three key technologies behind Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)

- Evolution of architectures: the shift from descriptor-based models to GNNs that explicitly account for geometric symmetries.

- Diversity of training data: the importance of balancing equilibrium data with non-equilibrium and unstable structures to prevent systematic softening.

- Practical validation methods: a growing emphasis on simulation stability and the reproducibility of physical properties, rather than static error metrics alone.

In particular, it is noteworthy that PFP, the model deployed in our universal atomistic simulator Matlantis, has adopted a strategy of aggressively learning from unstable structures since its initial development in 2021. This aligns well with the latest research trends, further reinforcing both the model’s forward-looking design and its soundness.

The emergence of MLIPs has dramatically expanded the accessible search space in computational chemistry. It has become possible to track complex physical phenomena involving thousands to tens of thousands of atoms in practical time while maintaining accuracy at the first-principles level. The progress of simulation technology by MLIPs is about to significantly change how materials development is conducted.

References

[2] A. P. Bartók et al., “On Representing Chemical Environments” Phys. Rev. B. (2013).

[3] Daisuke Okanohara, ”Symmetry and Machine Learning”, Iwanami Shoten, (2025)

[5] A. D. Kaplan et al., “A Foundational Potential Energy Surface Dataset for Materials” arXiv (2025).

[6] MatPES Dataset:https://materialsproject-contribs.s3.amazonaws.com/index.html#MatPES_2025_1/

[7] OMat24 Dataset:https://huggingface.co/datasets/facebook/OMAT24

[8] MPTraj Dataset:https://matbench-discovery.materialsproject.org/data/mptrj

[11]Kosuke Nakago “PFP: Neural Network Potential for Materials Discovery”, POL Seminar, (2022).(Only Japanese available.)

[12]So Takamoto “The technology and philosophy behind Matlantis”, Atlantis User Conference 2022. (Only Japanese available.)